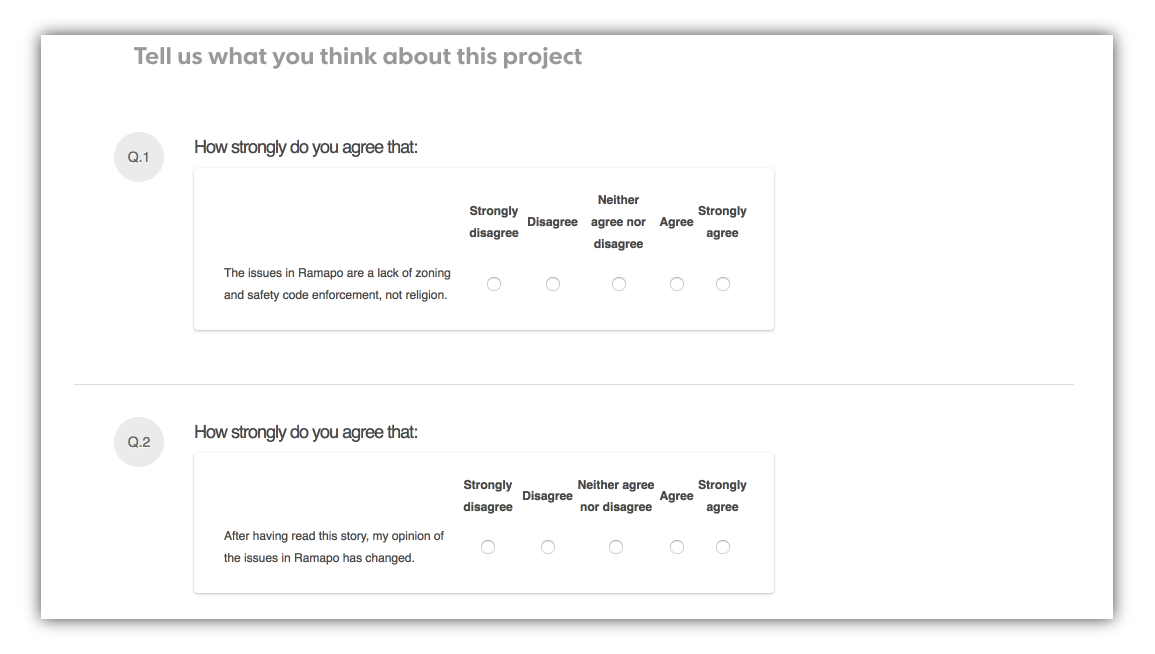

By Johanna Blakley Washington Post reporter Krissah Thompson contacted me recently asking me if I had any thoughts about Melania Trump’s use of social media. I thought it was a fascinating question and so I started digging into her Instagram and Twitter accounts. I must say, I found both feeds really dispiriting. I suspect that a lot of people who follow her closely and rate her highly might feel sorry for her. There is very little evidence that she is sharing anything remotely personal, which is what primarily attracts people to the social media feeds of celebrities and other powerful public figures. (The big exception, which might prove the rule, is her last Instagram post, a flirty close-up with a Santa hat.) You might assume that Melania Trump is simply uninterested in the public stage or is uncomfortable sharing her private life with the public, but her personal Twitter feed, which she hasn’t updated since election day, is filled with personal preferences and observations that feel quite intimate. So much so, that I’m pretty sure I could pick out a gift for her (and flowers!) that I know she’d like. That is what’s so powerful about these social platforms: they can make you feel as if you really know someone. But the carefully coiffed woman featured in the FLOTUS feeds seems distant and disconnected. I couldn’t help but wonder whether her approval rating is higher than her husband’s precisely because she withholds so much, which gives her the patina of dignity. Of course it’s tempting to compare Melania Trump’s social media presence with that of her predecessor, Michelle Obama. While the former first lady’s feed was also loaded with official events, she often spoke at those events, and through various media outlets, which allowed her to post material filled with her voice, her attitude, and her humor. She also had the habit of posting personal musings in the official FLOTUS account, which were differentiated from the rest of the feed with the initials “mo.” You don’t see any intimate asides from Melania Trump. The vast majority of the photos she posts are documentation of formal events: she’s basically caught on camera performing her duty. What you don’t tend to see is her looking into the camera, or trying to connect with the American public, as Michelle Obama does quite convincingly in her photos and videos. Our current first lady seems to see herself as someone to be seen – which makes sense given her professional modeling career – but strikes me as a bit chilling in her new role, which is endowed with tremendous cultural and political power. The big question is, will she ever choose to wield it? Read Thompson’s Washington Post article.  Claudia Gollub speaks during a public meeting on blockbusting, in a photo that ran with long-form journalism on a town’s conflicts. (Photo: Peter Carr/The Journal News) Claudia Gollub speaks during a public meeting on blockbusting, in a photo that ran with long-form journalism on a town’s conflicts. (Photo: Peter Carr/The Journal News) Journalists don’t as a rule have a specific impact in mind when we begin our journalism. We list project goals, but other than bringing awareness to an issue or event we do not identify what we’d like to see happen next. "After years of having the same tired, angry, circular discussion, we set out — in one project — to change the conversation." This is a story about the one time we did. Rockland County, just northwest of Manhattan, is one of New York’s fastest growing counties. Neighborhoods that used to feel suburban and bucolic now choke with high-density sprawl, multi-family homes rise in backyards next door, traffic is a problem and religious schools pop up on residential streets. This is the lede of our story for the Journal News and lohud.com: “A generation ago, there were few problems between Ramapo’s small ultra-religious Jewish communities and the gentiles and other Jews who made up the bulk of the town’s population. Things have changed. As the ultra-religious community has grown, Ramapo has become a flashpoint in a continuing conflict over what it means to live in the suburbs. … The conditions fueling that conflict are now threatening to spread beyond Ramapo’s borders. Surrounding communities have taken notice, and they are adopting measures aimed at heading off the strife that has become the norm for their municipal neighbor. No place, it seems, wants to become ‘the next Ramapo.’” People in Rockland County, one of two counties we cover at The Journal News and lohud.com, argue over this. Things get ugly. Reader comments on the stories we write turn hostile and border on anti-Semitism. No matter what the topic, the conversation inevitably devolves into “us” vs. “them.” But here’s the real problem, and it’s not religion: Ramapo’s loose zoning, lax enforcement of fire and building codes and largely unchecked development puts everyone at risk. We wanted to know: Do people understand what’s really happening in Ramapo? If we were to explain the issue — lay it out in long-form story, year by year and decision by decision — could we all (or most of us) finally agree? Could we change minds? If we could achieve consensus, would we stop arguing religion and start attacking the real problems? So, after years of having the same tired, angry, circular discussion, we set out — in one project — to change the conversation. We researched the story over several months. We talked to longtime residents, members of the Jewish community, government officials and the county’s Fire and Emergency Services coordinator. We wrote and rewrote, shot video and mapped the region. “Ramapo nears breaking point” is a long-form piece of explanatory journalism that laid out all of the problems that began decades ago. How we measured the story’s impact At the end of our story, we included a short survey to measure the impact of our explanatory journalism — to find out if we successfully proved that the issues in Ramapo are a lack of zoning and safety code enforcement, not religion. (We considered asking for opinion at the beginning of the story to gauge change at the end, but felt that would inhibit readership and we could accomplish what we needed with one survey at the end.) The survey was four questions, beginning with two easy Likert Scale queries: 1. How strongly do you agree that the issues in Ramapo are a lack of zoning and safety code enforcement, not religion? 2. How strongly do you agree that after having read this story, your opinion of the issues in Ramapo has changed? Then we expected a steep drop-off in answers to the final two questions because the first takes time and the second raises privacy concerns: 1. How have Ramapo’s issues impacted you? 2. What is your email address? We built the survey using PollDaddy because it prevents repeat responses and for the data it provides on the back end, including geolocation, a time/date stamp and referrer, and it assigns each respondent a unique PollDaddy ID. This helped us connect their answers from question 1 to question 2, and so on, and get a more complete picture of their response. We embedded the survey at the bottom of the long-form story. For two days, that was the only place you could find the survey; we didn’t embed it elsewhere or share it on social media. After two days we added it to our editorial, “Ramapo’s shoddy governance is by design.” Survey results Surprisingly, nearly 900 people responded. Here’s what they said: Do people understand what’s really happening in Ramapo? Yes. Most (67 percent) either agreed or strongly agreed with our explanation of the issues, with “strongly agree” ranking the highest (54 percent) Could we change minds? Yes. Of those 67 percent, 14 percent said our reporting convinced them, while 35 percent said they agreed beforehand. Finally, we believed we and the community could stop having the same conversation and instead move forward toward solutions. Emails. Almost a third — 29 percent — gave us their email address for follow-up. Sources and commentary. Even more surprising than the total number of respondents was the percentage of them — 38 percent — who also took the time to write about how Ramapo’s issues have impacted them. Hearing from homeowners, those who’ve moved away, educators, fire safety officials, people who have tried to move in but claim to have been denied housing gave us a list of future story ideas and sources. A few wrote to thank us for our reporting, for exposing the issues and doing so in such an unbiased way. A couple said we should have written this years ago. One called it “conversation-framing analysis” and others called for more discussion on the topic. One response shows how we raised awareness and encouraged civic involvement: “I live in a neighboring town and am concerned about Ramapo’s issues becoming issues here, too. So I will be paying more attention and doing what I can to ensure that we do not fall victim to the same lack of zoning and code enforcement that has plagued Ramapo.” What we learned

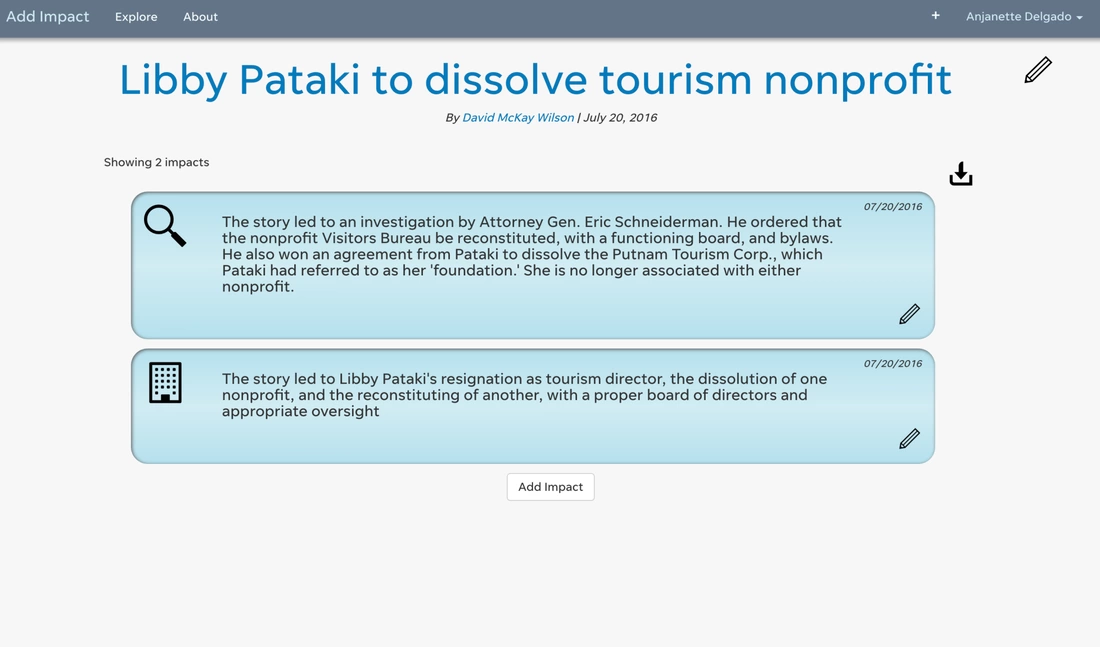

Anjanette Delgado is the digital director and head of audience for lohud.com and poughkeepsiejournal.com, part of the USA Today Network. Email: adelgado@gannett.com, Twitter: @anjdelgado. Special thanks to Lindsay Green-Barber of the Impact Architects, who helped with survey methodology. ###  By Laurie Trotta Valenti A case study by the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center’s Media Impact Project illustrates how one documentary series helped re-invigorate progressive groups following the 2016 elections, and may have lessons for media makers intent on social impact. The study of the EPIX series America Divided (which is available on Amazon and HULU) illustrates that documentarians can use innovative engagement campaigns to rally the public to action long after a program’s broadcast (if they were lucky enough to be broadcast!). America Divided producers took 10 strategic steps to engage citizens following broadcast. Some of the steps were tried and true, such as using celebrity prestige to attract attention, but others were innovative, such as editing several shorter, single-issue versions of the series that could be screened before niche groups. This helped to build coalitions around the project as well as re-energize a demoralized liberal base following the 2016 elections. The MIP study revealed that a key benefit was this re-invigoration of groups around the root causes of social injustice: the screenings and panel discussions gave activists a reason to assemble, to air their views and, more importantly, the paths to solutions. Specific actions that grew from these assemblages include canvassing, starting Social Media pages, creating petitions, signing-up for planned marches and rallies, as well as organizing additional meetings and screenings. The Case Study extracts 15 insights for media makers to create engagement around their work: 15 Tips for Media Makers to Keep Social Issues in the Public Eye 1. Think of broadcast as just the first step in your engagement campaign. 2. Forge partnerships with groups who can screen and promote your work. 3. Seek connections between your issue and any arts, civic, philanthropy or cultural groups and their own activist work. 4. Focus screening campaigns around one rallying issue. 5. Partner with regional PR firms that know the local players and issues and can unite disparate groups. 6. Be open to re-purposing edits that allow for issue or region specific coalitions. 7. Exploit celebrity power to cross-promote online, draw live audiences and create a relevant “face” for the issue. 8. Use screenings as forums for people to assemble, discuss and create community. 9. Engage audiences in panel discussions following screenings to promote deeper dialogue and create plans for social action. 10. Support learning with fact-based resources for deeper study. 11. Keep the momentum going by continuing to supply content to your partner groups. 12. Reach out to different-minded audiences to promote civil discourse. 13. Make the information in your documentary searchable online 14. Make certain screening partners can easily access your materials. 15. Keep your website current so that it becomes a source for news on your issues, and maintain ongoing dialogue with your digital audience. Here is a full copy of the report; please contact us at if you would like to be added to our mailing list. ### by Anjanette Delgado Measuring the audience response to a journalistic story usually means counting page views and unique visitors, yet that assessment falls short. At my Gannett newspaper in the suburbs north of New York City, we wanted to know more: What happened when we started asking questions (about a story)? After we published a story? When a key decision-maker or a crowd of people saw that story? We built an impact tracker to record not the clicks but the real-world change our journalism inspires. Did we spark a change in law, a donation, a citation or the dismissal of an unlawful employee? Did the family who lost their father’s Purple Heart years ago finally find it, with help from the crowd? Did we make a difference? If you’ve arrived at this post, I probably don’t need to say that journalism matters. For many of us, it’s a calling and a purpose and so on. But while print newsrooms especially have been hesitant to talk about the importance of our work lest we seem boastful, we need to drop the pretense and get comfortable reminding our readers, advertisers and subscribers of the impact we have on our communities — that is, if we wish to hold onto our relevance and our institutional heft. That’s why we at the Journal News and lohud.com built an impact tracker — to record not the clicks but the real-world change our journalism inspires. Examples of the impact we tracked The tracker primarily serves, but is not limited to, two types of journalism: explanatory and investigative. Whereas the purpose of explanatory journalism is to make something clear (improve understanding, change minds), the purpose of investigative journalism is most often to reveal the secrets held close by those in power. Documenting the impact of this journalism requires diligence and truthfulness on the part of the reporter; he or she must be able to prove, to a reasonable degree, that the change is the result of his or her work and not coincidence. It also requires time. The impact of a story might not be felt for months or years (for example, if a law is to be changed). Do it well, though, and you will have information like this at the ready:

How we use the information we collect

These stories of impact help our newsroom talk about our work in several important ways:

Why we deemphasize social media and what comes next Many news organizations and foundations studying impact rightly track social media shares to show reach, influence, and money well spent. While our tracker includes an option to explain the social media impact, we chose not to put our focus there for two reasons:

We started the tracker two years ago as a Google Form because it was simple to spin up and revise as we learned more about impact tracking and how it can help our newsroom. (Much credit for inspiring this first version goes to the wise and thoughtful Lindsay Green-Barber, founder of The Impact Architects and formerly of the Center for Investigative Reporting.) Today Version 2.0 of the tracker is a Ruby on Rails web application developed by Avram Billig to populate a database. Journalists manually add impacts and tie them to stories, and we can then filter and view by story, author, date, impact, etc. As reporters from multiple newsrooms add their work, it gets categorized and stored in a PostGreSQL database that we query to discover the analytics of impact over time. We’re sharing this version of the software with other USA Today Network newsrooms, and we’re beginning to think about 3.0 features such as connecting impact to traditional analytics and data visualizations. Each iteration of the software is a chance for greater understanding. Questions about the tracker or how we’re studying impact? Email me at adelgado@gannett.com or message me on Twitter @anjdelgado. The tracker has been a team effort from the start. Avram Billig turned my visions for the tracker into reality and is the reason reporters and editors think this is all much easier than it really is. Find Avram on Twitter @aabillig. Traci Bauer gave us the support and freedom to develop the tracker, and she helped shape many of its features. She is the vice president/news for The Journal News/lohud.com and The Poughkeepsie Journal. She believes empowering a community with strong journalism is the best way to build loyalty among audiences, and tracking their actions helps measure our own success. Email Tracy at tbauer@gannett.com and on Twitter @tbauer. Anjanette Delgado is the digital director and head of audience for lohud.com and poughkeepsiejournal.com. You can reach her at adelgado@gannett.com and on Twitter @anjdelgado. ### By Johanna Blakley

The Norman Lear Center and the Paley Center for Media held an event on November 2 exploring how technology and storytelling are raising awareness about important social issues. I gave a presentation (which you can watch here) addressing how we can connect the dots between media exposure and social or political action. Summarizing results from the Lear Center’s impact studies of the documentary film Waiting for “Superman,” the narrative feature film Contagion, and the Guardian’s global development news website, I explained how mixed methods research can be used to assess changes in knowledge, attitudes and behavior from media exposure (You can read full-length reports here). The evening started with a very timely panel discussion about how new technologies are informing and invigorating public discourse about social issues. Justin Osofsky, Vice President of Media Partnerships and Online Operations at Facebook, discussed how “humbled” the organization was by the profound impact that Facebook Live video streaming has produced. Wesley Lowery, National Reporter at The Washington Post and author of the forthcoming They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement, explained how his fluid use of Twitter, Snapchat and Periscope transformed his journalistic process. Raney Aronson-Rath, Executive Producer of Frontline, weighed in on the expanding use of VR among newsgatherers, and her “Aha!” moment at MIT’s Open Documentary Lab. Jennifer Preston, Vice President of Journalism at the Knight Foundation, which sponsored this event, joined the panel in a nuanced conversation about the difference between journalistic ethics and online community ethics, which are becoming more deeply interwoven as citizens move to social media platforms for news. The second panel of the night addressed the impact of storytelling in entertainment, bringing together the grandfather of social issue TV, Norman Lear; Kenya Barris, creator of black-ish; and Gloria Calderon Kellett, Co-Showrunner of the Netflix reboot of Lear’s classic One Day at a Time. Moderated by Marty Kaplan, the group addressed the critical need for entertaining stories about real people and real problems on screens large and small. Sensitive to the historic lack of diversity on primetime TV, Barris and Kellett discussed the need to dislodge the notion that there’s one monolithic experience for each ethnic group. By injecting their own lived lives into their storytelling, all three writers felt that they could trigger conversations that could lead to social change. Feeding a habit is much easier than breaking one.

"In less than two years we doubled our web traffic. At a time when everyone's web traffic was rising, we grew much faster than the industry average."Consider the morning news habit. We wake up, reach for our smartphones before even getting out of bed, and check to see what’s happening in the world. Whereas once that was a printed newspaper or morning TV, now it’s push alerts, Facebook posts, Twitter feeds and destination news sites. The technology has changed, but our habit remains. News organizations working to attract and keep audiences (that’s pretty much all of us, right?) can increase their traffic overall by publishing for the morning habit — posting stories ahead of the spike. A few years ago I was the editor of Gannett’s Salinas Californian newsroom. One of my first steps in our digital transformation was to build a Post and Readership Comparison chart, which showed when readers were on our site and when we published. The trend was dramatic — we published just as everyone was leaving. Very little of what was on our site for the morning news habit — the 8 a.m. spike — was new; most had been written the afternoon before on a print deadline. When reporters saw the chart they started asking questions, then thinking, then planning what they could publish ahead of the morning spike. Some rearranged their work hours. Sunita Vijayan, who was then our courts reporter, decided she’d come to work earlier, publish a couple of quick posts about what court cases she’d be covering that day, and include a note to readers to check back later for updates. “Early and often,” as we hear in Mic’s editorial meeting. “In less than two years we doubled our web traffic. At a time when everyone’s web traffic was rising, we grew much faster than the industry average.” I’ve used this Post and Readership Comparison chart in a couple of newsrooms since then, and each time it inspires a change in how we publish and leads to an increase in traffic. Now, what does your traffic pattern look like? Learn your spikes — mobile, desktop and social media — and test this idea to see if it works for you. And even more than increasing traffic (page views), does it intensify your stickiness (return visits, average time spent per person)? Stickiness leads to loyalty, to subscribers, donors, members and brand ambassadors — whatever your long-term goal. Big, breaking news drives traffic regardless of time of day and shouldn’t be held, but for everything else there’s a spike waiting to be explored. This is my first post for USC Annenberg’s Media Impact Project. Each month over the course of the year, my colleague Rob Gates and I will discuss finding, measuring and studying audience, tracking impact, and wherever else the year and the technology lead us. Suggestions are most welcome. Follow us on Twitter (@anjdelgado and @rjgatesontheweb) or drop me an email at adelgado@gannett.com. Anjanette Delgado is an audience analyst at Gannett and http://lohud.com. She also writes for USC Annenberg’s Media Impact Project. ### |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed