|

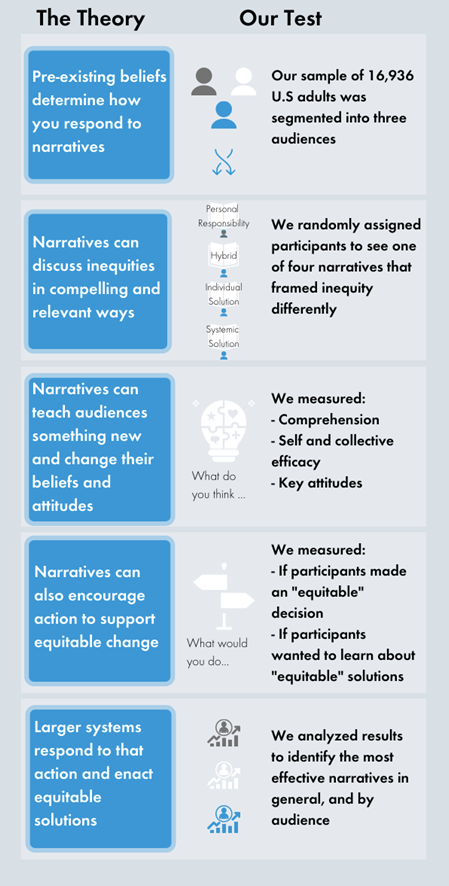

By Behavioural Insights Team This piece has been cross-posted from the Behavior Insights Group’s webpage. To read the original post, please visit their website. In 2015, the USA Network show Royal Pains featured a brief storyline about a transitioning transgender teen and the challenges she faced. The episode aired during a period of unprecedented media attention on the transgender community. The transgender rights movement was gaining momentum, but also experiencing backlash. Unlike other popular shows at the time (e.g., Transparent), Royal Pains did not routinely address LGBTQIA issues. In the midst of this charged environment, the episode gave the Royal Pains audience – who represented a broad ideological spectrum – an opportunity to engage with transgender rights as a story, rather than a policy. This narrative approach was impactful. Researchers from University of South California’s (USC’s) Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism teamed up with the school’s Norman Lear Center (NLC) – a nonpartisan center of research and innovation that studies and shapes the impact of media and entertainment on society – to assess the episode’s impact. They compared Royal Pains viewers who saw the episode with regular Royal Pains viewers who had not yet seen it. The researchers found that viewing this episode was associated with more supportive attitudes towards transgender people and relevant policies. Further, this eleven-minute fictional narrative was more influential than news stories, including those about the Caitlyn Jenner transition, which was widely covered at the time. Royal Pains isn’t an isolated example. Stories provide an accessible way of presenting complex issues. They make it easier for us to relate to people from different backgrounds. Stories’ ability to transport us can also make us less likely to push back against the assumptions in a narrative. They can even change health behaviors; researchers have found that story-based interventions can increase rates of cervical cancer screening and encourage safer sex. Given their power, we wanted to explore how narratives could be used to tell a new story about inequities, particularly in the context of health. Dominant narratives in the U.S. focus on personal responsibility, suggesting individuals are primarily responsible for their health outcomes through their choices and behavior. But evidence shows that health outcomes reflect the broader conditions individuals live, work, and play in. Therefore, addressing health disparities requires a shift in: thinking, individual action, and structural change. Only then can we ensure that “everyone has a fair and just opportunity” to be healthy, happy, and productive. Increasingly, narratives in media and entertainment address social determinants of health, but storytellers and policymakers need more evidence to understand what types of narratives work, and for whom. In 2019, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, BIT partnered with Norman Lear Center’s Media Impact Project (MIP) to test the impact of four types of narratives on audience mindsets and behaviors. We found that (1) “hybrid” narratives are useful for a wide audience; (2) narratives are more effective when they specifically make connections between conditions, policies, and outcomes; and (3) we identified avenues for further research on online platforms. Read on for more details on what we did and our findings and visit MIP’s Narratives of Health Equity website for more detail on their research. We designed an online experiment to test the impact of four narratives on mindsets and behaviors In an online Predictiv experiment, we tested the impact of four text-based narratives on a large sample of 16,936 adults in the U.S. Survey participants were segmented into three “audiences” composed of people with similar ideologies and media habits. The four narratives were based on existing entertainment narratives that MIP identified through qualitative research. Participants were randomized to read one of four narratives about Nathan, a fast-food worker who goes to a barbecue and is exposed to COVID-19. The narratives vary in how they frame the causes of and solutions for his subsequent health and financial issues; more detail on these narrative frames can be found below. See Figure 1 for an excerpt from the “systemic solution” narrative:

One behavioral measure asked participants to decide how to allocate a hypothetical medication to prevent COVID-19. Options included: first come first serve, a lottery, or equity-driven allocation to high-risk groups first.

Regardless of the narrative they read, most participants said they would allocate the medication to high-risk groups, but they differed in who they considered high-risk. Those who read any of the three hybrid narratives were more likely to say that not having health insurance – which was directly mentioned in the story – should classify someone as high-risk and therefore make them more likely to receive the medicine. Hybrid narratives also increased support for policies, like paid sick leave, that would address Nathan’s specific circumstances. Narratives that offered a systemic solution increased support for related topics that weren’t explicitly mentioned like the suspension of rent payments and guaranteed unemployment benefits. However, those narrow attitude shifts didn’t transfer as strongly to more abstract attitude changes on broader topics of justice and government responsibility. While these findings suggest that specificity is important, to understand how to make narratives as impactful as possible, further research could explore what types of attitudes (e.g., about specific policies or about abstract beliefs) best predict behavior. Online experiments are cost-effective ways of getting early findings, with populations of interest, before moving to complex field trials. Online experiments allow us to test theories and approaches without real-world risks, which, given the power and reach of popular media narratives, could be significant. We suggest using this approach to confirm and expand on these findings to test video formats, narratives with different main characters, or narratives that more explicitly discuss or model the behaviors of interest. For more information on this project, please contact BIT. Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. ### by Anjanette Delgado The simplest of gestures — someone needed help and someone else offered it — began many years ago in David Rodríguez’s childhood. Rodríguez, 27, is a multimedia journalist at The Salinas Californian, a local newsroom in a Northern California city known for its lettuce fields and migrant farm labor from Mexico, nestled in a valley called “The Salad Bowl of the World.” He moved to Salinas from Aguascalientes, Mexico when he was 8. “This project was a long time in the making,” Rodríguez told me as he explained “Living in the Shadows.” “Up until last year, I never got to focus on it due to difficulties I faced growing up as I adjusted to life in the United States with my single farm-working mother.” His difficulties were the same as the Salvadors, one of two families featured in his project. Food insecurity. Overcrowded housing. Education inequities. And “low-paying work that kept my mom away for long hours,” he said. “My life with her motivated me throughout this whole project.” While his past may have driven Rodríguez to tell their story, it’s his present — his job taking pictures at the newspaper company, Gannett, that includes USA Today — that eventually made a difference for the Salvadors.

“Living in the Shadows” is a four-part series published from June to October 2020. It documents the plight of the Salvadors and other immigrant families living in Monterey County following the outbreak of COVID-19. Rodríguez and The Californian produced the series in partnership with CatchLight, a visual media nonprofit based in San Francisco.

During the run of the project, several strangers who saw it gave food to the Salvadors. This type of help, from a reader or viewer to the subject of the story after that story is published, is sometimes called “benefit to source” and classified as impact on individuals. “Groceries began to pile up with each trip to the car,” Rodríguez wrote. “Bags lined the counters. Cans were stacked upon each other. Breakfast, lunch and dinner had options rather than routine.” The simplest of gestures. Yet to the Salvadors, it meant so much. “It was the first time I experienced an abundance of food,” said Resi Salvador, 19. “I was shocked.” Megan Gong, 52, reached out to The Californian shortly after reading the first story and asked if she could donate food to the Salvadors and their daughter Resi, who was featured. “The Salvadors and I are living proof that journalism changes lives,” Gong told Rodríguez. “It took courage for Resi to share her story with you and if I didn't have a digital Salinas Californian subscription, I wouldn't have read the Salvadors' story and had the opportunity to help a family in need.” Rodríguez’s project reminds me of the story of “Harvest of Shame,” a 1960 CBS and Edward R. Murrow report documenting the substandard living conditions of farmworkers from Florida to upstate New York. Both relied on the power of visuals to move people to action; “Shame” moved policy makers, while “Shadows” moved individuals. David Lowe, a producer of the CBS report, told Time magazine this a week after the show aired: “We hoped that the pictures of how these people live and work would shock the consciousness of the nation." To get a better sense of what Rodríguez hoped would happen going into his project and in an attempt to understand why it made a difference amid a global pandemic when so many others are struggling too, I asked him about his process. Here are his answers, with limited editing: The Salinas Californian published the whole series. Who else, if anyone, reported on these families? USA Today shared the first story in the series nationwide, which was about food insecurity for low-income farm working families at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. People reached out to The Californian asking how to help. Tell me about that experience and when it happened. The first person to reach out was a woman from Texas, asking how to help after the food insecurity story was published in USA Today. I was in awe. I couldn’t believe it because that is our hope when we do these stories — that they create this kind of impact when people read them. That woman sent diapers to the family featured in the story, as well as non-perishable items like chips and peanut butter she thought the children would enjoy. This first donation really helped the family during the start of the pandemic. Another woman who lives locally reached out shortly after asking if she could provide ongoing donations of food to the family for the duration of the project. Over five months, she dropped off hundreds of dollars of meat and produce so that the family of seven could have nutritious food. The family was in awe as much as I was because they didn’t think this kind of help was possible. It absolutely helped them survive the pandemic. The simple necessities of food and diapers made them so happy. That’s where the title for the final story, “Our stories have power,” came from. What other feedback did you receive? There were dozens of responses, but one quote that really stood out to me was from a respected community leader and longtime Salinas resident, who said: “Sharing the truth has made all the systems in this community reflect on how they provide service...It has shown us not only where we need to grow as a resource center, but emphasized more importantly the need to lean on these stories to inform policy and practice...So grateful the community has you to capture our voice.” That meant the world to me, because I’ve seen the struggles of this community firsthand. Growing up, I set out to be a voice for others. I didn’t know that journalism would be my avenue to do that because I picked it up at a late age, but I’m glad I was able to achieve my goal and help shine light on this community. This problem didn’t require institutional change to solve, just a phone call from one person to another offering to buy food. And yet so many people are hungry in the pandemic, so many people are struggling to meet the most basic of needs. Why do you think these stories made a difference? Many stories have been written about the pandemic, but the visuals really set these stories apart. There aren’t many local photographers covering the pandemic, so for community members to see the consequences of the pandemic for people less fortunate than them, I think it really hit a note. A lot of people can relate to the struggles of farm-working families, so it makes it easier for some people to help. This is a community that takes care of one another. Visuals gave a face to hardships of the pandemic. People have heard about the problems farm workers face, but they have not seen their lives up close. Getting a look into their homes made it impossible to ignore the disparities in income, food security, education and housing. What role did USA Today play in the project? With the first story, USA Today provided editing support so that it could be the best it could possibly be. With all of the extra eyes, it was a well-written piece with visuals that made an impact. USAT has a national audience, so the story had a platform larger than I am used to. It allowed people from all over the country to learn about the plight of farm workers in California. What role did CatchLight play? CatchLight had one of the most important roles. I met with Jenny Stratton, my CatchLight mentor, weekly to discuss the progress of my project. If it wasn’t for her visual editing skills, my photo sequence would not have been as cohesive. When it came to editing photos and arranging them in a thoughtful way, Jenny’s feedback was essential. I also got to meet with the other fellows to get ideas and feedback, so it was a beautiful learning environment that was free of judgement. It allowed me to do my best work. Has the response from this project changed how you’ll plan future projects? If so, how? It definitely has. Before this project, I loved photography but I was not comfortable with writing. I really learned the importance of having someone to discuss your project with. Having extra sets of eyes to help you edit will dramatically increase the quality of your work. If I involve my community into my work process, my project will shine even brighter than I thought it could. --- This paragraph from a follow-up story to the series, in which Rodríguez shares the impact it has had, stays with me: Resi said she was initially shocked by the outpouring of support and kindness. Today, she said she feels gratitude and confidence in telling her story of being an indigenous woman with farm working immigrant parents. “Our stories have power,” she said. “I’m very grateful for this opportunity that journalism has given me.” The series Coronavirus: Feeding the family gets tough when work is threatened Stretched Thin: Housing plight intensified by COVID-19 pandemic California essential workers in a silent fight with COVID-19 It took COVID-19 to remedy inequities in Monterey County schools Follow-up story about impact 'Our stories have power': Stories, visuals bring aid to Salinas families Project explainer In partnership with CatchLight, a Bay Area visual storytelling nonprofit organization, this reporter — David Rodríguez — committed to a long-term project documenting the impact of COVID-19 on farm working families in Salinas. The series followed two Salinas families over a seven-month period. Contact Rodríguez at (831) 269-9363 or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter: @visualdavid. Subscribe here to support local journalism. CatchLight’s impact statement “Through the medium of visual storytelling, CatchLight exists to create powerful transformations in the way people understand complex issues of justice, tolerance, and the common good. To better understand our impact, we rigorously measure the difference we make across three dimensions: artist impact, community impact, and social issue impact.” Anjanette Delgado is the senior news director for digital at the Detroit Free Press and freep.com, part of the USA Today Network that also includes The Salinas Californian. She was the editor of The Californian from 2008-2010. Email: [email protected], Twitter: @anjdelgado. ### |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed