|

By Tracy Van Slyke, Chief Strategy Officer at the The Pop Culture Collaborative, and Erica Watson-Currie, PhD, Cross-posted from Medium Before we get into frameworks and explanations, let’s name the big question in the room: When it comes to the work of narrative change, how do you measure narrative impact? For field members, it’s a question they not only ask themselves in order to understand the impact of their work, but also to prove their work to obtain resources. For funders, it’s the question they are genuinely asking to understand the work better, but that they also need to answer to justify moving those resources to field members. This question, or variations of it, is necessary — and one that everyone, in their own individual ways, is trying to answer. But the lack of cohesion, alignment, and shared direction around impact evaluation is undermining the ability of field members to measure individual and collective impact and limiting funders from moving the scale of resources necessary to advance transformative narrative change. This is why in 2020, the Pop Culture Collaborative partnered with the USC Norman Lear Center’s Media Impact Project to lead the research and design for a useable, multi-pronged evaluation framework for field members and funders in the pop culture narrative change field to track, learn from, and evaluate progress in the work to transform narrative oceans in our quest to creating a just and pluralist culture. And the result is a new beta framework: INCITE — Inspiring Narrative Change Innovation through Tracking and Evaluation. This new learning and evaluation framework has been developed to equip the pop culture narrative change field — comprised of artists, values-aligned entertainment leaders and companies, movement leaders, cultural strategists, narrative researchers, philanthropic partners, and more — with a shared methodology to unearth learnings and track short and long-term impact, at both the individual and collective levels. This launch of the beta INCITE framework is the first step in a road testing process set to take place over 2024 to make it useful and usable by field members and funders alike. Read on to learn more about its development and how to get involved. Four Barriers to Effective Narrative Change Evaluation When the Pop Culture Collaborative publicly launched as a first-of-its-kind pop culture narrative change donor fund and learning community in 2017, we were constantly asked about how we measure narrative change impact. In the ensuing years, we have moved more than $30 million dollars to help scaffold the pop culture narrative change field and build its narrative power; launched the Becoming America Fund, the first multi-year, multi-million dollar initiative to fund and coordinate a narrative network of pop culture narrative change practitioners; and developed and shared foundational narrative change methodologies. These areas of work have required our team to stretch and experiment with strategies for narrative impact measurement within our grantmaking programs and extending to our impact in the field and ecosystem. In tandem, the Media Impact Project at the University of Southern California’s Norman Lear Center has spent over 10 years collecting, developing, and sharing approaches for measuring the impact of media in order to better understand the role that media plays in changing knowledge, attitudes, and behavior, and ultimately, in shifting culture. The Media Impact Project’s work includes program evaluations investigating audience awareness, reception, and responses to media content, and research into why and how the content achieved its impacts. The question that continues to plague us both: why is it so hard for all of us — field members, funders, and evaluators alike — to get on the same page about narrative change impact evaluation? With our collective years of work and bird’s eye view of the practitioner and philanthropic fields, we have identified four key barriers: We’re focused on measuring the drops, not the narrative ocean. At the Collaborative, we understand that every day we are each immersed in an ocean of narratives, ideas, and cultural norms. This is why, as Pop Culture Collaborative CEO Bridgit Antoinette Evans has written, our work is not to “shift the narrative” on a particular issue, but instead to activate narrative systems — coordinated systems of mental models, narrative archetypes, and immersive story experiences — that work together to normalize pluralist behaviors and values in the U.S. This narrative system approach accelerates our ability to transform the narrative oceans we are all immersed in. Dimple Abichandani, former Executive Director of General Service Foundation and one of the Collaborative’s “founding mothers,” summarized this contradiction well at ENTERTAINCHANGE: Philanthropy, the Collaborative’s 2019 gathering of 100-plus narrative change funders. “If we’re trying to change the ocean, why are we measuring the drops? We need to measure the ocean.” The most common evaluation approach is to focus evaluation efforts on measuring the “drops” in the ocean — a singular story, film, television show, or impact campaign. It is extremely important to evaluate and, most importantly, learn from those initiatives in relation to the goals, and scale, of those individual efforts. But to understand if and how enduring narrative change is happening, we need to track and evaluate both the drops as well as how they add up to the transformation of a narrative ocean over time. There isn’t a shared approach that accounts for the diversity of narrative change methodologies and strategies. There are at least two key reasons for this. First, while strategic communications and culture change are both types of narrative change work, their evaluation approaches are different (note 1). These two types of work require different types of expertise, strategies, and infrastructure, yet expected outcomes and applied metrics are often conflated. Right now, a mismatch of appropriate impact evaluation metrics is hindering our ability to track and understand the impact of different types of narrative change approaches. If we continue to conflate the two, then we’re setting ourselves up for blurring the learnings, undermining the impact analysis, and limiting the future activation of both narrative change approaches. Second, culture change narrative indicators don’t match the diversity of approaches. Looking specifically at the pop culture narrative change field, there are a multiplicity of narrative change efforts. For example, a social justice organization’s narrative change work may focus on moving mass audiences around a specific idea, while another initiative is deeply focused on supporting intersectional BIPOC artists to build their creative power and career longevity within the entertainment industry. The appropriate indicators don’t currently exist, or aren’t accurately applied, to those different sets of strategies and intended outcomes. This doesn’t even account for the stage of the work (For instance: Is it new? Has the work been in place for years?). We need to have clear, shared methodology and metrics that are adaptable and applicable to different narrative strategy approaches and stages. Evaluation efforts aren’t tracking a field’s ability to build and wield narrative power. Connected to the previous point, evaluation inquiries often start by focusing solely on external narrative outcomes such as reach and impact on audiences. Instead, we need to begin at a different point: evaluating the narrative drivers — field growth and industry transitions — that create the power base to transform a narrative ocean. Too often skipped are the capacity development, relationship and partnership building, strategy-informing research and narrative intelligence gathering, and experiments and learning that form the foundation of an organization, company, network, and/or field’s ability to have the methodology and capacity to activate narrative change. In addition, we’re not tracking the efforts of what it takes to create transformational power shifts inside a narrative industry, like Hollywood, to create just working conditions and the authentic, needed storytelling that can help transform narrative oceans. This includes the ability to make decisions, move resources, and control the means of production and distribution from within narrative industries. These narrative drivers are often the determining cause for the advancement or impediment of narrative goals and strategy — and so evaluation efforts need to account for them as actual outcomes to learn about and evaluate over time. If philanthropy wants impact evaluation, we need to help field members pay for it. Field members do want to evaluate their work, not to just prove its worth for the next grant proposal, but to understand what and how the narrative change strategies they’re designing and/or implementing are working towards their culture change goals. But as the Media Impact Project well knows, few practitioners in the pop culture narrative change field have the resources — both the funding and the shared knowledge base — to even locate relevant research literature that could inform an impact evaluation, much less conduct consistent, ongoing evaluation of their individual work. Often, field members have defaulted to reporting only reach and engagement metrics and don’t have the resources to engage in broader data-gathering, relying on individual anecdotes or inconsistent participant feedback to attest to their effectiveness. These findings are difficult to generalize or synthesize into systemic impact analysis. Philanthropy must identify how to match narrative change support with needed evaluation support. Knowing these barriers have hindered the field’s ability to learn from and evaluate their narrative change work, and for funders to build the needed investment strategies, we went to work. Meet INCITE: A Beta Framework for Narrative Change Evaluation In 2020, the Pop Culture Collaborative partnership with the Media Impact Project led to the investigation and co-design of a multi-pronged field and funder learning framework and tools that could start to solve for these barriers. The first result: Connections and Accomplishments, a first-of-its-kind network mapping (note 2) of the pop culture narrative change field, which set a baseline for understanding the connectivity and strength of the field and its evolving relationships. Some key findings set the stage for evaluating the growth of the pop culture narrative change field over time:

The Media Impact Project integrated these lessons into their multi-year information gathering and research review process that included:

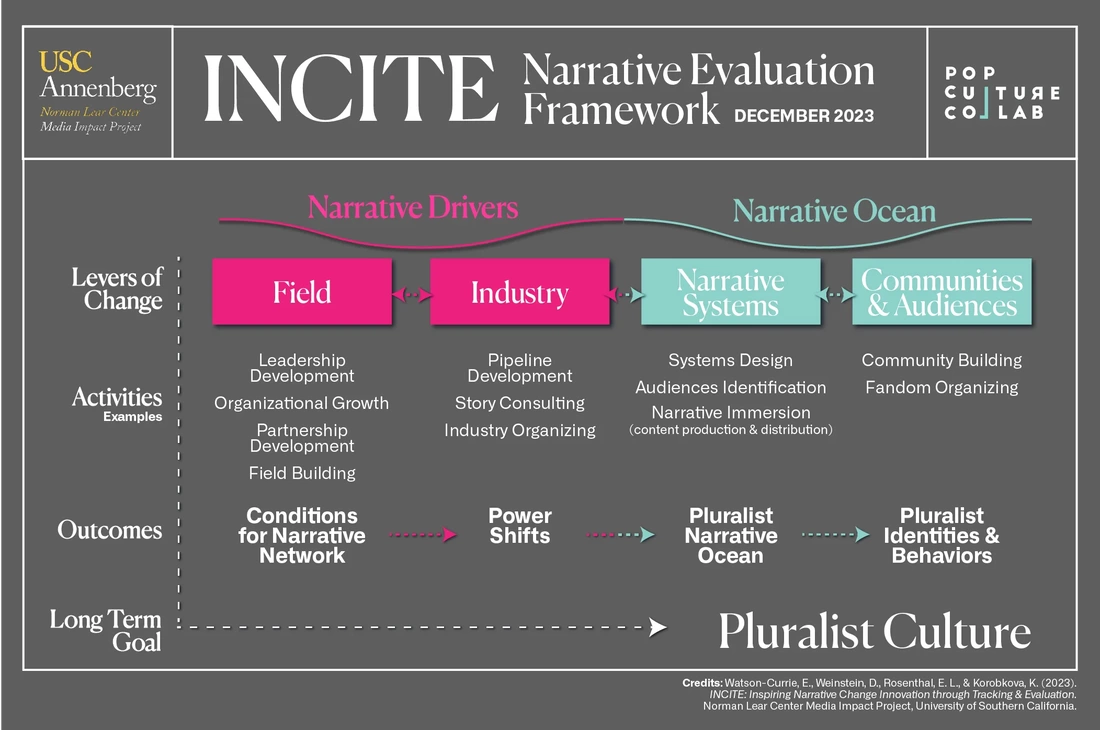

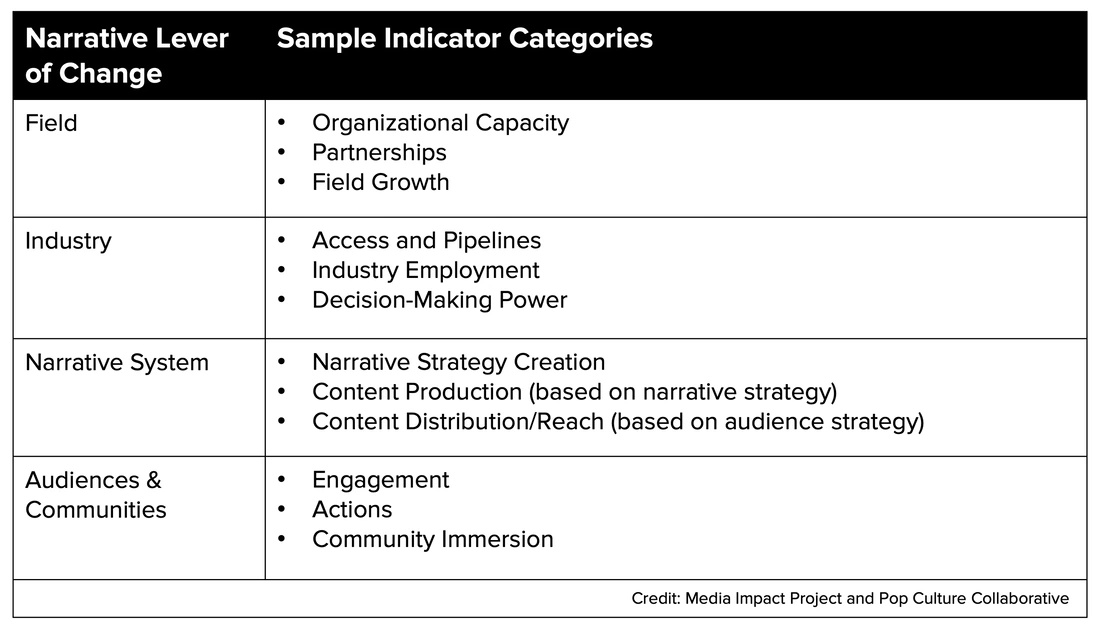

During this time, Media Impact Project was also engaged in research projects with other pop culture narrative change field members (e.g., Define American, Caring Across Generations, futurePerfect lab, IllumiNative, National Domestic Workers’ Alliance, Color of Change). These engagements informed knowledge about field members’ interests, activities, and aspirations. The result of this multi-year investigation and design process is INCITE — Inspiring Narrative Change Innovation through Tracking and Evaluation — an adaptable framework designed to equip both field members and funders with shared definitions, measurable objectives, learning questions, indicators, and metrics to understand and assess the impact of their individual culture change efforts as well as the field’s progress towards seeding the narrative ocean with pluralist ideas, narratives, and norms. The INCITE framework below reflects our ultimate goal to create the conditions necessary to generate narratives that will ignite pluralist awakenings and a desire for social justice within audience members, which, in turn, lead to long-term culture change. The INCITE Narrative Evaluation Framework to the Media Impact Project and Pop Culture Collaborative. With this as our goal, there are two major categories for evaluation: Narrative Drivers and the Narrative Ocean. Across these categories are four levers of change within two buckets: Narrative Drivers holds the field and industry levers, and the Narrative Ocean holds the narrative systems and audiences and communities levers. Let’s dive into the framework. Narrative Drivers are the people and infrastructure that make narrative immersion in pluralist ideas, cultural norms, and stories possible. These drivers have two key levers for change that merit evaluation: field and industry. When field and industry analysis is conducted together, we can evaluate the pop culture narrative change field’s ability to grow and wield its narrative power, creating the conditions to transform narrative oceans over time. Within the FIELD, we can evaluate and track both:

Within INDUSTRY, we can track, within a specific narrative industry (e.g., Hollywood) the impact of narrative infrastructure investments, such as the results of:

Within NARRATIVE SYSTEMS, we can understand how core pluralist ideas — carried by pop culture stories and experiences through a coordinated network of artists, producers, cultural strategists, and more — are taking hold in our cultural waters, including indicators and metrics that track and analyze:

For example, short-term outcomes at the field-level may include organizational capacity metrics, such as the number of team members and the diversity of their expertise dedicated to activating a narrative strategy. Longer-term outcomes might include partnership development and field building indicators, such as the quality, depth, and results of sustained relationships and collaborations over time.

It’s important to note that the INCITE framework is not intended to be read linearly. The activities and levers of change generally build upon one another, but there can be many different pathways to influence various audiences, industries, and culture. For instance, some field members may aim to indirectly influence narratives by way of leveraging the talent pipelines that feed the entertainment industry (i.e., industry-lever with narrative-level outcomes). Other field members may do the reverse, by creating content that sparks power shifts within Hollywood (i.e., narrative-lever with industry-level outcomes). How Does INCITE Work in Practice? The first step: As you look at the levers of change — field, industry, narrative systems, and audiences and communities — where do you see yourself, or your grantee partners, operating? Some might fit inside just one lever or across multiple levers. Even just this quick analysis will indicate that a one-size-fits-all evaluation approach doesn’t reflect the complexity and multiple layers for building narrative power and creating narrative immersion. With INCITE, field members and funders can identify themselves within the lever(s) that authentically reflect their work and apply the corresponding indicators and metrics to learn from and evaluate their impact. We can then avoid the situation of — let’s say, for example — operating within the industry lever and exclusively trying to apply audience metrics to measure your impact. This framework is only the beginning. Media Impact Project has also started to curate an initial set of project planning resources, suggestions for progress tracking indicators, and learning questions to help connect activities to outcomes or indicators of impact. Alternatively, when applied with an outcomes-orientation, INCITE offers a shorter pathway to options for practitioners and methods to assess types of impact and document project outcomes at different levels (e.g., field, industry, narrative systems, and/or audiences and the changes their work is trying to achieve). While INCITE has been designed for the pop culture narrative change field and built around what we understand inside the entertainment industry, we hope that this framework expands to become inclusive of other industries working at the intersection of narrative and social change. Join Us in Testing INCITE In 2024, the Pop Culture will take INCITE and narrative change evaluation to the next level. We are inspired and motivated by the feedback we have received so far. During the design process, a small group of field members, including culture change strategists and leaders within the entertainment industry and social justice movements, were able to review and provide feedback. “I have spent a lot of time … reflecting and remarking on the fact that we [are] really far from having any sort of infrastructure in place to actually evaluate this work, so it’s amazing to see a skeleton and a process for that.” — Ishita Srivastava, Chief of Narrative and Culture Change at Caring Across Generations Over the next year, the Pop Culture Collaborative will organize and support a subset of grantee community and philanthropic partners to both test and then iterate this beta framework and the associated indicators to best support individual and collective learning and impact evaluation needs. Over time, we will work with our field and philanthropic partners to develop tools and resources that will track the evolution of the pop culture narrative change field and transformation of narrative oceans over time. Our vision: to have shared evaluation vocabulary, methodology, framework, and metrics that will help us in our work of co-creating a just and pluralist culture where everyone inherently belongs. JOIN US: If you are a field member and/or philanthropic partner interested in testing INCITE in your own narrative change work, please reach out to [email protected]. For example, some organizations with whom we shared early drafts of these resources, like the United Kingdom’s Power of PoP Fund, have already begun to adapt the framework for their own purposes. We are in the process of developing testing, use, and attribution guidelines to ensure the integrity of the model while in this beta stage and beyond. We request that you do not use this framework without being in conversation with us. Article contributions from Dana Weinstein, MA, Ksenia Korobkova, PhD, Erica Rosenthal, PhD, and Johanna Blakley, PhD. Footnotes:

This article has been crossposted from LinkedIn.

By Dana W, Soraya Giaccardi, and Kristin Eunjung Jung, Media Impact Project The past few years have ushered in a wave of Asian-led entertainment content, with films and TV shows like Everything Everywhere All At Once, Beef, and Never Have I Ever enjoying both critical and commercial success. These stories offer nuanced and authentic takes on universal themes like rage, love, and family, while also embracing cultural specificity through the lens of their leading Asian characters. Because Asian characters have historically invoked racial stereotypes (think Sixteen Candles’ Long Duk Dong), race-agnostic roles – or those in which a character’s race/ethnicity is mentioned briefly or not at all – have often been championed as indicators of progress towards a future in which Asian actors can play any role (think Sandra Oh in Killing Eve). But recent content demonstrates how race-central roles, or those in which racial/ethnic identity are a central part of the storyline or in understanding a character’s motivations, can also be vehicles for authentic, humanizing, and successful stories (think Meilin in Turning Red). To understand how race centrality plays out in contemporary content, the USC Norman Lear Center and Gold House joined forces on a study examining the most prominent Asian characters in popular scripted streaming titles of 2022. We were struck by three main findings:

As we look towards the future, we hope to see Hollywood move beyond a “one size fits all” approach towards assessing representation by embracing complexity over binaries and encouraging a full spectrum of roles that reflect a range of identities and experiences —something journalist Rebecca Sun called “a lesson in representation 2.0 or even 3.0.” Together with our friends at Gold House, we look forward to carrying these conversations into 2024. By Shawn Van Valkenburgh

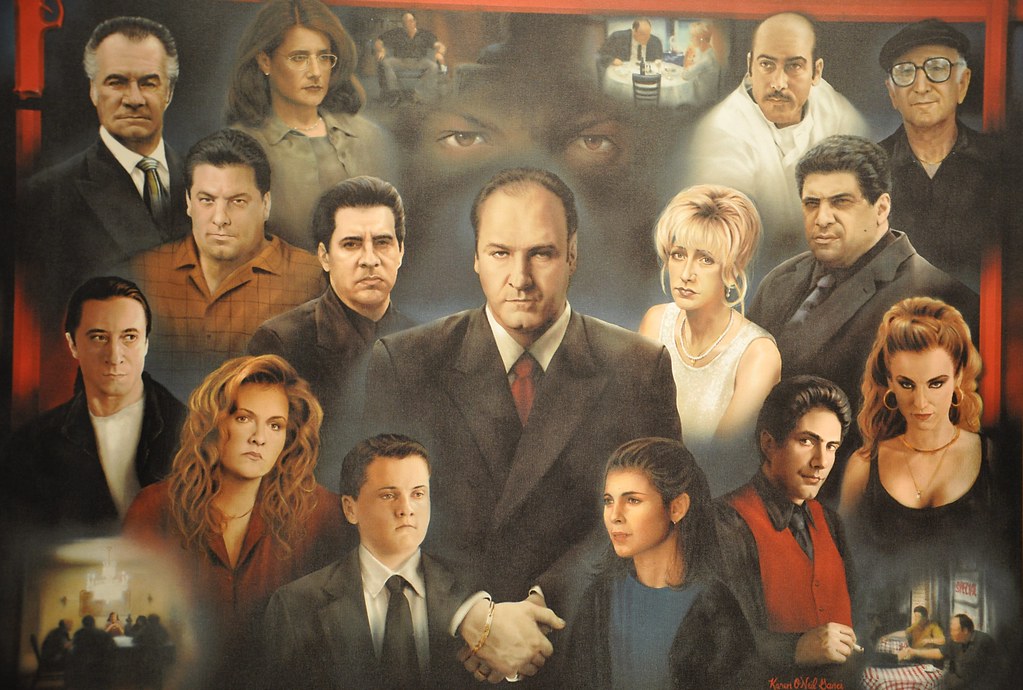

The past several years have witnessed a renewed interest in The Sopranos, the HBO series that inaugurated the era of prestige television. In September 2021, a New York Times headline announced that “Every Young Person” was watching the series. Although the show concluded in 2008, Warner Media reported that viewership has more than doubled since March 2019. On one level this resurgence should not be surprising, considering the show’s skill in addressing broad-appeal themes like power, loyalty, violence, crime, and so on. Its central conceit is a delicious hook: Mob boss Tony Soprano seeks therapy from mild-mannered psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi. And its writing is still considered the gold standard for prestige drama. In 2016 Rolling Stone declared it was the best TV show of all time, in part due to the richness and complexity of its characters. Esquire credits “The depth of its characters across the board,” while The New Yorker notes that its “characters arrive and take full human shape.” There is much for fans and critics to love about Sopranos characters, and that should be a good enough explanation for its second wind. On another level, the Sopranos renaissance provokes further explanation. Why this series in particular—in competition similarly acclaimed dramas, like Mad Men for instance—and why now? The New York Times attributes some of this renewed popularity to the “dirtbag left,” a brand of progressivism that embraces vulgarity online and openly disdains political centrism. While it is mostly populated by online slacktivists, the term “dirtbag left” is usually associated with snarky podcasts like Red Scare, Street Fight Radio, and above all, Chapo Trap House. An influx of Sopranos memes and references will be familiar to those who occupy some of Twitter’s niche comedy and political spaces. The hosts of Chapo regularly deliver Sopranos references to their millions of listeners. In their book, Chapo praise The Sopranos with uncharacteristic sincerity, calling it “just as challenging and thought-provoking” as art from other media. But beyond the caliber of its writing, Chapo appreciate The Sopranos for its resonance with modern politics and social commentary. Co-host Felix Biederman praises its depiction of societal collapse, “not as a romantic, singular, aesthetically breathtaking act of destruction” but as a slow descent into barbarism: “you sit down for 18 hours a day, enjoy fewer things than you used to, and take on the worst qualities of your parents while you watch your kids take on the worst qualities of you.” This is the essence of NYT’s explanation for youthful interest in the show: The Sopranos expresses a pessimistic view of America that resonates with disappointed millennials. But I’d like to point out another way in which The Sopranos resonates with current events and disaffected youths. It has to do with Melfi’s doomed attempt to rehabilitate Tony. The Chapo book finds political overtones in this relationship, as Melfi represents “the ultimate and final failure of educated, cosmopolitan liberals to meaningfully confront—let alone reform—evil.” In this reading, Tony represents the dark side of America in the 21st century. He is racist, violent, and misogynist. Although he appears to be a warm and loving father, he is willing to murder if doing so serves his financial interests. Dr. Melfi, meanwhile, presents a polite and ineffectual resistance to Tony’s violence. Though she struggles at times with the ethics of treating such a criminal, her only real impact on Tony is to provide him with a psychological language that he uses to manipulate others. Critic Emily Nussbaum observed that through his therapy, Tony “gained more sophisticated tools to cope with life. But he became a better mobster, not a better man.” For Chapo, Melfi’s impotence represents the political status quo, which seems unable to effectively confront social problems like war, climate change, and systemic racism. Melfi ultimately decides that Tony is irredeemable after she reads The Criminal Personality, a real-life academic book that constructs a psychological archetype for criminological purposes. This book was published in the 1970’s, a time when social sciences were being used to justify a burgeoning war on drugs and the proliferation of prisons. Its central thesis tells us that criminals are irredeemable, and it seems to describe Tony perfectly. While he may show some signs of compassion — he seems to care about babies and animals — he only uses therapy to bludgeon those around him: “For the criminal, therapy is just another criminal operation.” After reading the book by lamplight in her bedroom, Melfi ends up agreeing with her ex-husband, who initially dismissed Tony as evil: “Call him a patient. Man’s a criminal, Jennifer. And after a while, finally, you’re going to get beyond psychotherapy, with its cheesy moral relativism, finally you’re going to get to good and evil. And he’s evil.” Shortly after coming to this realization, Melfi recommends that Tony seek therapy elsewhere. I would suggest that this doctor-client relationship taps into common anxieties about the source of social problems in America. Are these crises caused by evil, or by well-meaning people who make mistakes? The former view lends itself to dismissal, punishment, and confinement — as the authors of The Criminal Personality might advocate — while the latter lends itself to some kind of empathy or understanding. According to some dirtbag left discourse, attempts to find compassion for people who cause suffering end up rationalizing their harmful behavior, in the way that Tony’s therapy enables his criminal activities. Some would point out the dangers of trying to “understand” those who cause social harms, insofar as these well-meaning efforts might distract us from seemingly obvious solutions. (It is a moment of strange bedfellows, then, that the dirtbag left would end up resonating with a criminological theory that runs counter to progressive efforts to reform or abolish the prison system.) The source of evil in our society is something like a psychopath that can’t be reasoned with. On these grounds, perhaps we can find some common ground between the popularity of The Sopranos and the success of Don’t Look Up, the surprise Netflix hit that delivers a coarse message about climate change. This film compares our ecological crisis to a meteor on a collision course with Earth, and suggests that much of our public discourse only serves to distract us from important issues. What was it about this film that made it the most successful Netflix film ever? Perhaps there is something about vulgar diagnosis that some millennials would find refreshing in a time when “nuance” can be used to equivocate and avoid meaningful action. If there is any common denominator between The Sopranos and Don’t Look Up, I think it indicates that millennials are sick of malarkey. Perhaps these cultural phenomena show that many view popular discourse as a cover for the simplicity of real-world solutions. For all the nuance of Sopranos writing, then, what resonates most may be is its clear and direct theses about the criminal sources of social problems. Shawn Van Valkenburgh is a research specialist with the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center's Media Impact Project. ###  Reporter Jessica Miller. (Francisco Kjolseth) Reporter Jessica Miller. (Francisco Kjolseth) By Anjanette Delgado I’d been researching the role of impact producers in journalism (we need more of these, by the way) and documentary films when I came across new legislation in Utah to regulate its troubled-teen industry. The story behind the law involves a journalist, two lawmakers in two states, a celebrity influencer, an activist group and an impact producer all working on the same issue. Their individual yet connected actions challenge us to think about the roles journalism and funding play in action, the importance of taking the whole system into account and, in the end, what motivates everyone to keep going. *** One Sunday night in May 2019, a dozen students began fist fighting at a troubled-teen center in southern Utah. Cops were called. The SWAT team showed up. The night ended in multiple injuries, and more than half of the dozen rioting students were charged.“We were so reactive to this news,” said Jessica Miller, a reporter at The Salt Lake Tribune newspaper. She needed to know more, to know what led to the riot. “What could be learned if we were more proactive?”So she spent the time between then and now — minus what it took and still takes to cover the pandemic — being more proactive about that story. Digging until she uncovered one of the most outrageous stories in her two-plus years investigating Utah’s troubled-teen industry: a girl in zip ties forced to sit in the cold, dirty water of a horse trough. Back then, in 2019, the troubled-teen industry fell into a gap between beats. Miller started learning more by submitting public records requests. She reported deeply on staff members, and eventually the school with the riot — Red Rock Canyon in St. George — shut down. She sought out and earned a fellowship in data journalism from the University of Southern California Annenberg School of Journalism that included funding, training and mentorship. “We started looking at this industry as a whole — how much other states are spending to send kids here,” Miller said. She filed a large records request. “Inspection reports from the office of licensing,” she said. “$6,000.” Public records are public, yes, but governments are allowed to charge for the labor and copying costs of satisfying requests. Newsrooms have limited budgets for records or sometimes can’t pay at all. “We couldn’t pay it,” Miller said. “At first we didn’t do it. We tried to figure out other ways to do it.” Right around then — in September 2020 — Paris Hilton’s documentary film, This is Paris, premiered on YouTube. ***

Rebecca Mellinger, a USC grad, is an impact producer working with Hilton. In the documentary, the actress and influencer comes to grips with her own time spent at one of these troubled-teen centers in Provo, Utah. “I was verbally, mentally and physically abused on a daily basis,” Hilton said. “I was cut off from the outside world and stripped of all of my human rights.” Hundreds of people emailed Hilton every day, and more posted online. “All of these survivors are taking to social media in the thousands,” Mellinger said. Clearly they had momentum — momentum they could use to help stop abuse from happening at these facilities, to help save at-risk children now and in the future, and to support abuse survivors. Mellinger and Hilton brainstormed a three-pronged approach:

The work is nearly full-time (sometimes they’re busier than others) and has been going on for months. The public awareness campaign is what led her to Miller. *** Remember the $6,000? Miller wanted to use it not just to get the public records but also to build the first free, searchable database of reports on violations at Utah’s troubled-teen treatment centers. “After doing this work for more than a year or so, getting so many emails from parents asking ‘I want to send my kid to this place, what do you know?’” Miller said, “it showed us how much of a need there was.” Mellinger asked how they could support Miller’s work, and though they were working on the same issue, journalism’s code of ethics requires keeping an arm’s length distance from those who are trying to influence the news. “She offered to pay but we felt uncomfortable because she’s an activist,” Miller said. Instead, The Salt Lake Tribune launched its first crowdfunding campaign (using MoonClerk) and set a goal of raising $10,000 — the cost of the records plus coding, etc. Miller wrote a story explaining why: “It is easier for a person to go online and find the latest inspection for a restaurant than it is to find reports on whether a youth residential treatment center is keeping vulnerable children safe.” In less than 24 hours, they raised $11,000 from more than 130 donors, including Hilton. “When I think about the database, I think it showed us that we can fundraise in this somewhat nontraditional way. … that that’s a possibility,” Miller said. “Clearly there was a need in this community and it was wider than just our subs [subscriber] base.” The fundraiser took place in October, the records arrived in February, and after some data cleaning the database published in March 2021. That’s when Miller learned about the horse trough. *** It started as a routine police call. In June 2018, a 17-year-old girl living at a treatment center for troubled teens had hit a staff member in the face during a therapy session involving horses. But when deputies arrived at the small ranch in southwest Utah, staff said the suspect was waiting “in the trough.” Confused, the deputies walked back to the corral. There they found a girl sitting in a tub of dirty water up to her torso. When the girl stood, they saw her hands were zip tied behind her back. One deputy yelled for a staffer to get her out of the water, according to the police report. Another cut her loose. The girl told deputies she had tried to run away from Havenwood Academy, a 16-bed treatment center located a few miles from the horse property. When a staffer had tried to stop her, she had thrown a punch, she told them. By the time the deputies arrived, she had been in zip ties for about 30 minutes, she told them, and in the horse trough for about 20. — From “A girl, her hands zip tied, was forced to sit in a horse trough,” March 26, 2021. In the story, Miller quite quickly turns from this incident at Havenwood to the systemic problem of Utah’s approach to regulating the youth treatment industry — investigations, but no individual or institutional penalties. “It’s kind of been our goal all along, past the riot, (of) trying to tell stories of individual instances and put it in the greater backdrop of industry, particularly in Utah,” she said. Miller’s editor, Lauren Gustus, shared the story in an email thanking Tribune readers. “The woman who pioneered putting girls in troughs remained Havenwood’s equine director until she quit of her own volition,” Gustus wrote. “She left around the time Jessica and a small team of journalists published a database that included infractions at Havenwood and elsewhere. This database was created with your support — donors and subscribers helped pay the thousands of dollars in open records fees we had to pay to secure the infraction reports.” *** In the meantime, Hilton organized more than 100 fellow survivors in a march past Provo Canyon School. Utah Sen. Mike McKell reached out to discuss legislation, Mellinger said. Sen. Sara Gelser of Oregon, a state that sent some of its foster kids to these centers, including Red Rock and Provo, became perhaps the most outspoken lawmaker. (These aren’t Utah kids, Miller told me. Ninety percent of them are from out of state.) Finally, in March 2021, Utah passed McKell’s bill requiring troubled-teen facilities to be investigated four times a year and to report when they administer medication to a patient. Gov. Spencer Cox signed it, saying “first and foremost, it’s about protecting the lives, especially, of our young people in these programs.” The law went into effect in May, two years after students rioted, less than a year after Hilton rallied in Provo and a little more than three months after it was introduced. It was the state’s first legislation in 15 years to address mistreatment at youth facilities. “It happened so quickly, but people were ready to talk about it where they weren’t two years ago,” Miller said. In an April email to readers, Gustus quoted Sen. McKell from the first committee hearing: “There’s a natural tension between the press and the Legislature from time to time. I think Jessica Miller has been fantastic. I don’t know where she is in the room, but I think she’s done a fantastic job with her investigative reporting at The Tribune, finding some of the failures in the state of Utah. And I think that’s to be appreciated.” *** Breaking this story down to its parts, we can begin to see how a major industry treating mostly out-of-state kids landed on Utah’s public policy agenda:

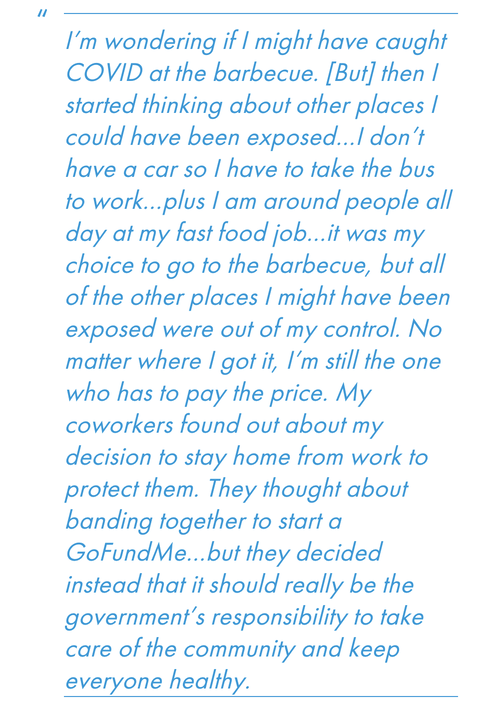

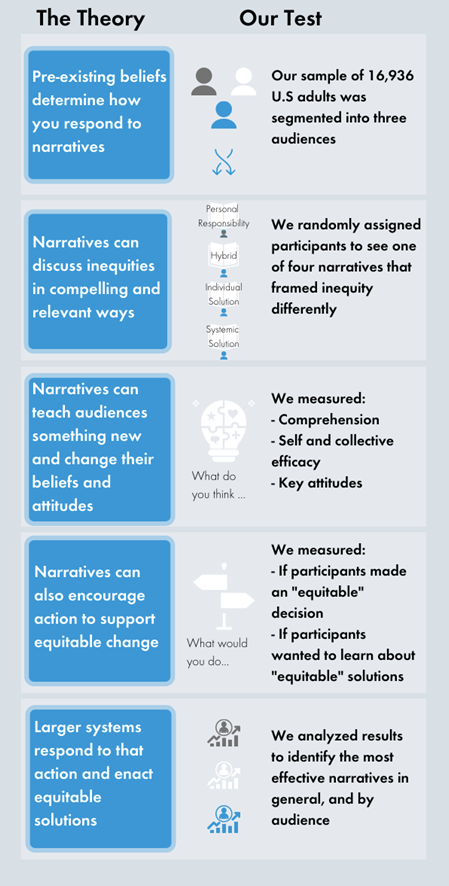

“I do hope through this case study of Paris … (that) anyone with a platform looks at this and does want to pursue something they care about as well,” Mellinger said. Mellinger and Hilton are working with Breaking Code Silence to get a national bill passed and keep people engaged in the issue through Change.org and email updates. “We’ve really made it a priority to create a coalition of organizations,” Mellinger said. They still want Provo Canyon School shut down, an early goal of their campaign, but their focus has shifted more toward policy. “We’ve got a long road ahead, but obviously the momentum is there,” Mellinger said. “An impact producer morphs based on the project,” Mellinger said. “That’s the joy of it. It’s about the solution.” Miller, for her part, continues to report the stories of abuse and keeps a “very close eye” on whether the new law is being followed. She’s collaborating with KUER public radio and APM Reports on a podcast about her investigation called Sent Away. It will be released in late fall. “The hard part about this industry as a whole is you can call anything therapy,” she said. “No one’s questioning ‘hmm, is that therapy?’” That is, no one was. More: Inside Utah’s troubled teen industry: How it started, why kids are sent here and what happens to them To support Miller’s work and The Salt Lake Tribune, go to sltrib.com/donate. Anjanette Delgado is the senior news director for digital at the Detroit Free Press and freep.com, part of the USA Today Network. Email: [email protected], Twitter: @anjdelgado. ### By Behavioural Insights Team This piece has been cross-posted from the Behavior Insights Group’s webpage. To read the original post, please visit their website. In 2015, the USA Network show Royal Pains featured a brief storyline about a transitioning transgender teen and the challenges she faced. The episode aired during a period of unprecedented media attention on the transgender community. The transgender rights movement was gaining momentum, but also experiencing backlash. Unlike other popular shows at the time (e.g., Transparent), Royal Pains did not routinely address LGBTQIA issues. In the midst of this charged environment, the episode gave the Royal Pains audience – who represented a broad ideological spectrum – an opportunity to engage with transgender rights as a story, rather than a policy. This narrative approach was impactful. Researchers from University of South California’s (USC’s) Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism teamed up with the school’s Norman Lear Center (NLC) – a nonpartisan center of research and innovation that studies and shapes the impact of media and entertainment on society – to assess the episode’s impact. They compared Royal Pains viewers who saw the episode with regular Royal Pains viewers who had not yet seen it. The researchers found that viewing this episode was associated with more supportive attitudes towards transgender people and relevant policies. Further, this eleven-minute fictional narrative was more influential than news stories, including those about the Caitlyn Jenner transition, which was widely covered at the time. Royal Pains isn’t an isolated example. Stories provide an accessible way of presenting complex issues. They make it easier for us to relate to people from different backgrounds. Stories’ ability to transport us can also make us less likely to push back against the assumptions in a narrative. They can even change health behaviors; researchers have found that story-based interventions can increase rates of cervical cancer screening and encourage safer sex. Given their power, we wanted to explore how narratives could be used to tell a new story about inequities, particularly in the context of health. Dominant narratives in the U.S. focus on personal responsibility, suggesting individuals are primarily responsible for their health outcomes through their choices and behavior. But evidence shows that health outcomes reflect the broader conditions individuals live, work, and play in. Therefore, addressing health disparities requires a shift in: thinking, individual action, and structural change. Only then can we ensure that “everyone has a fair and just opportunity” to be healthy, happy, and productive. Increasingly, narratives in media and entertainment address social determinants of health, but storytellers and policymakers need more evidence to understand what types of narratives work, and for whom. In 2019, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, BIT partnered with Norman Lear Center’s Media Impact Project (MIP) to test the impact of four types of narratives on audience mindsets and behaviors. We found that (1) “hybrid” narratives are useful for a wide audience; (2) narratives are more effective when they specifically make connections between conditions, policies, and outcomes; and (3) we identified avenues for further research on online platforms. Read on for more details on what we did and our findings and visit MIP’s Narratives of Health Equity website for more detail on their research. We designed an online experiment to test the impact of four narratives on mindsets and behaviors In an online Predictiv experiment, we tested the impact of four text-based narratives on a large sample of 16,936 adults in the U.S. Survey participants were segmented into three “audiences” composed of people with similar ideologies and media habits. The four narratives were based on existing entertainment narratives that MIP identified through qualitative research. Participants were randomized to read one of four narratives about Nathan, a fast-food worker who goes to a barbecue and is exposed to COVID-19. The narratives vary in how they frame the causes of and solutions for his subsequent health and financial issues; more detail on these narrative frames can be found below. See Figure 1 for an excerpt from the “systemic solution” narrative:

One behavioral measure asked participants to decide how to allocate a hypothetical medication to prevent COVID-19. Options included: first come first serve, a lottery, or equity-driven allocation to high-risk groups first.

Regardless of the narrative they read, most participants said they would allocate the medication to high-risk groups, but they differed in who they considered high-risk. Those who read any of the three hybrid narratives were more likely to say that not having health insurance – which was directly mentioned in the story – should classify someone as high-risk and therefore make them more likely to receive the medicine. Hybrid narratives also increased support for policies, like paid sick leave, that would address Nathan’s specific circumstances. Narratives that offered a systemic solution increased support for related topics that weren’t explicitly mentioned like the suspension of rent payments and guaranteed unemployment benefits. However, those narrow attitude shifts didn’t transfer as strongly to more abstract attitude changes on broader topics of justice and government responsibility. While these findings suggest that specificity is important, to understand how to make narratives as impactful as possible, further research could explore what types of attitudes (e.g., about specific policies or about abstract beliefs) best predict behavior. Online experiments are cost-effective ways of getting early findings, with populations of interest, before moving to complex field trials. Online experiments allow us to test theories and approaches without real-world risks, which, given the power and reach of popular media narratives, could be significant. We suggest using this approach to confirm and expand on these findings to test video formats, narratives with different main characters, or narratives that more explicitly discuss or model the behaviors of interest. For more information on this project, please contact BIT. Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. ### by Anjanette Delgado The simplest of gestures — someone needed help and someone else offered it — began many years ago in David Rodríguez’s childhood. Rodríguez, 27, is a multimedia journalist at The Salinas Californian, a local newsroom in a Northern California city known for its lettuce fields and migrant farm labor from Mexico, nestled in a valley called “The Salad Bowl of the World.” He moved to Salinas from Aguascalientes, Mexico when he was 8. “This project was a long time in the making,” Rodríguez told me as he explained “Living in the Shadows.” “Up until last year, I never got to focus on it due to difficulties I faced growing up as I adjusted to life in the United States with my single farm-working mother.” His difficulties were the same as the Salvadors, one of two families featured in his project. Food insecurity. Overcrowded housing. Education inequities. And “low-paying work that kept my mom away for long hours,” he said. “My life with her motivated me throughout this whole project.” While his past may have driven Rodríguez to tell their story, it’s his present — his job taking pictures at the newspaper company, Gannett, that includes USA Today — that eventually made a difference for the Salvadors.

“Living in the Shadows” is a four-part series published from June to October 2020. It documents the plight of the Salvadors and other immigrant families living in Monterey County following the outbreak of COVID-19. Rodríguez and The Californian produced the series in partnership with CatchLight, a visual media nonprofit based in San Francisco.

During the run of the project, several strangers who saw it gave food to the Salvadors. This type of help, from a reader or viewer to the subject of the story after that story is published, is sometimes called “benefit to source” and classified as impact on individuals. “Groceries began to pile up with each trip to the car,” Rodríguez wrote. “Bags lined the counters. Cans were stacked upon each other. Breakfast, lunch and dinner had options rather than routine.” The simplest of gestures. Yet to the Salvadors, it meant so much. “It was the first time I experienced an abundance of food,” said Resi Salvador, 19. “I was shocked.” Megan Gong, 52, reached out to The Californian shortly after reading the first story and asked if she could donate food to the Salvadors and their daughter Resi, who was featured. “The Salvadors and I are living proof that journalism changes lives,” Gong told Rodríguez. “It took courage for Resi to share her story with you and if I didn't have a digital Salinas Californian subscription, I wouldn't have read the Salvadors' story and had the opportunity to help a family in need.” Rodríguez’s project reminds me of the story of “Harvest of Shame,” a 1960 CBS and Edward R. Murrow report documenting the substandard living conditions of farmworkers from Florida to upstate New York. Both relied on the power of visuals to move people to action; “Shame” moved policy makers, while “Shadows” moved individuals. David Lowe, a producer of the CBS report, told Time magazine this a week after the show aired: “We hoped that the pictures of how these people live and work would shock the consciousness of the nation." To get a better sense of what Rodríguez hoped would happen going into his project and in an attempt to understand why it made a difference amid a global pandemic when so many others are struggling too, I asked him about his process. Here are his answers, with limited editing: The Salinas Californian published the whole series. Who else, if anyone, reported on these families? USA Today shared the first story in the series nationwide, which was about food insecurity for low-income farm working families at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. People reached out to The Californian asking how to help. Tell me about that experience and when it happened. The first person to reach out was a woman from Texas, asking how to help after the food insecurity story was published in USA Today. I was in awe. I couldn’t believe it because that is our hope when we do these stories — that they create this kind of impact when people read them. That woman sent diapers to the family featured in the story, as well as non-perishable items like chips and peanut butter she thought the children would enjoy. This first donation really helped the family during the start of the pandemic. Another woman who lives locally reached out shortly after asking if she could provide ongoing donations of food to the family for the duration of the project. Over five months, she dropped off hundreds of dollars of meat and produce so that the family of seven could have nutritious food. The family was in awe as much as I was because they didn’t think this kind of help was possible. It absolutely helped them survive the pandemic. The simple necessities of food and diapers made them so happy. That’s where the title for the final story, “Our stories have power,” came from. What other feedback did you receive? There were dozens of responses, but one quote that really stood out to me was from a respected community leader and longtime Salinas resident, who said: “Sharing the truth has made all the systems in this community reflect on how they provide service...It has shown us not only where we need to grow as a resource center, but emphasized more importantly the need to lean on these stories to inform policy and practice...So grateful the community has you to capture our voice.” That meant the world to me, because I’ve seen the struggles of this community firsthand. Growing up, I set out to be a voice for others. I didn’t know that journalism would be my avenue to do that because I picked it up at a late age, but I’m glad I was able to achieve my goal and help shine light on this community. This problem didn’t require institutional change to solve, just a phone call from one person to another offering to buy food. And yet so many people are hungry in the pandemic, so many people are struggling to meet the most basic of needs. Why do you think these stories made a difference? Many stories have been written about the pandemic, but the visuals really set these stories apart. There aren’t many local photographers covering the pandemic, so for community members to see the consequences of the pandemic for people less fortunate than them, I think it really hit a note. A lot of people can relate to the struggles of farm-working families, so it makes it easier for some people to help. This is a community that takes care of one another. Visuals gave a face to hardships of the pandemic. People have heard about the problems farm workers face, but they have not seen their lives up close. Getting a look into their homes made it impossible to ignore the disparities in income, food security, education and housing. What role did USA Today play in the project? With the first story, USA Today provided editing support so that it could be the best it could possibly be. With all of the extra eyes, it was a well-written piece with visuals that made an impact. USAT has a national audience, so the story had a platform larger than I am used to. It allowed people from all over the country to learn about the plight of farm workers in California. What role did CatchLight play? CatchLight had one of the most important roles. I met with Jenny Stratton, my CatchLight mentor, weekly to discuss the progress of my project. If it wasn’t for her visual editing skills, my photo sequence would not have been as cohesive. When it came to editing photos and arranging them in a thoughtful way, Jenny’s feedback was essential. I also got to meet with the other fellows to get ideas and feedback, so it was a beautiful learning environment that was free of judgement. It allowed me to do my best work. Has the response from this project changed how you’ll plan future projects? If so, how? It definitely has. Before this project, I loved photography but I was not comfortable with writing. I really learned the importance of having someone to discuss your project with. Having extra sets of eyes to help you edit will dramatically increase the quality of your work. If I involve my community into my work process, my project will shine even brighter than I thought it could. --- This paragraph from a follow-up story to the series, in which Rodríguez shares the impact it has had, stays with me: Resi said she was initially shocked by the outpouring of support and kindness. Today, she said she feels gratitude and confidence in telling her story of being an indigenous woman with farm working immigrant parents. “Our stories have power,” she said. “I’m very grateful for this opportunity that journalism has given me.” The series Coronavirus: Feeding the family gets tough when work is threatened Stretched Thin: Housing plight intensified by COVID-19 pandemic California essential workers in a silent fight with COVID-19 It took COVID-19 to remedy inequities in Monterey County schools Follow-up story about impact 'Our stories have power': Stories, visuals bring aid to Salinas families Project explainer In partnership with CatchLight, a Bay Area visual storytelling nonprofit organization, this reporter — David Rodríguez — committed to a long-term project documenting the impact of COVID-19 on farm working families in Salinas. The series followed two Salinas families over a seven-month period. Contact Rodríguez at (831) 269-9363 or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter: @visualdavid. Subscribe here to support local journalism. CatchLight’s impact statement “Through the medium of visual storytelling, CatchLight exists to create powerful transformations in the way people understand complex issues of justice, tolerance, and the common good. To better understand our impact, we rigorously measure the difference we make across three dimensions: artist impact, community impact, and social issue impact.” Anjanette Delgado is the senior news director for digital at the Detroit Free Press and freep.com, part of the USA Today Network that also includes The Salinas Californian. She was the editor of The Californian from 2008-2010. Email: [email protected], Twitter: @anjdelgado. ### By Johanna Blakley

Remember my TED.com talk, Lessons from Fashion’s Free Culture? Well, a Fellow at Harvard’s Nieman Center, Tomer Ovadia, interviewed me recently about what lessons the news industry might learn from the fashion industry. We discussed the many surprising parallels between the two and where the future might lead. Listen to the podcast now and let me know what you think! Original Reporting · Ep. 5 – “Start From the Ashes” Johanna Blakley is the Managing Director of the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center. ### By Anjanette Delgado

Journalists are good with messes. Problems make for interesting stories with lots of layers, complicated characters and usually thick narrative drama. Designing for impact, however, sometimes means sweeping the mess aside and clearing a path to action. We talk about information needs; this need is for information that helps me navigate my life. Take this story about Port Chester, New York: Gabriel Rom had been on the Port Chester reporting beat for two years when he learned about the village’s election problems. Port Chester is about an hour north of Manhattan by train. Its people are working middle class, sandwiched between the wealthy communities of Greenwich, Connecticut, and Rye, New York. For more than three centuries, immigrants have been coming there from around the world — first Italy, then Poland, then Portugal and now Central and Latin America. Cross Westchester Avenue north from quaint, upscale Rye and it feels like you’re back in the city again, surrounded by high-density housing and bodegas. Eighty percent of the village’s school children are non-white Latino, one of the highest percentages in the state. Voter turnout here hovers at around 10 percent. Back in 2006, while its people were majority Hispanic, its leaders weren’t. That obvious disparity was the subject of much litigation. In 2009, a federal judge found that the at-large way Port Chester elected trustees — one vote per voter — violated the Voting Rights Act because it diluted the voting strength of Hispanics. In its place the village adopted cumulative voting, a rarely used process where one voter is allowed to cast multiple votes for a candidate. Now, in 2018 when Rom was on the beat for lohud.com, where I also worked, the village was coming out from under court supervision. Voters had to decide for themselves whether to keep cumulative voting or try something else. Instinct told Rom this decision was an important story — the community needed his help — but experience told him it wasn’t going to top the Chartbeat real-time analytics dashboard. “It was an interesting case, interesting history and we’ve got a news hook” — a referendum coming, Rom said. “I saw it as a clear opportunity to connect all this history and background information with a specific news hook. “This is a story that’s important from a civic education perspective — a story about how our democracy works, a story that needs to be told because it impacts thousands of people. Just because it wasn’t our paying audience didn’t mean it wasn’t a story worth telling.” “It wouldn’t be the responsible thing to do to ignore the story,” he said. The project

Early turning points Clarity: One key decision we made early on was to consult with the Democracy Fund. Josh Stearns, a friend and director of the fund’s Public Square Program, introduced us to their elections expert, Tammy Patrick. Patrick helped us see that the story wasn’t the mess but helping people understand a complicated voting process that to many, especially those new to the U.S., could sound like some sort of scam. “Before I spoke to her I was way into the weeds on court filings from decades ago … snowed in on all the material,” Rom said. “This is what led to that explainer piece. It just felt like let’s try and do the work that citizens don’t have the time to do … show people why it matters, not just how crazy it is.” The Democracy Fund’s interest in the project also gave Rom the support he needed to pursue a project where he knew he wouldn’t be able to use page views as a proxy for value. “You need confidence as a reporter when you do stories like this,” Rom said. “People saying it was a good story and you need to do it the right way was a good energy booster.” Collaboration: Another critical early decision was to collaborate with Univision to reach more Hispanics, especially those who speak Spanish. This showed the story was important enough for multiple news organizations to get involved. “We wanted to hit Port Chester residents but also Hispanic community leaders throughout the state and nation,” Rom said. Lessons learned

“If we were to do it again, I do think it’s possible to get people to engage who don’t,” Rom said. “But it would have taken more direct outreach. … “I kind of compare it to a political campaign. You can’t overestimate the power of just getting out and knocking on doors.” The access was there — in restaurants, etc. — to print and hang fliers, he said. “If we had done that, I feel like the story would have taken a real turn.” Impact

Outcome Voters decided, 746 to 429, to continue the cumulative voting method. “It was the least controversial, the most rational” decision, Rom said. And it was an informed decision. Impact stories USA TODAY’s investigation of reverse mortgages helped spark reforms which stand to help 90,000 seniors. “The piece USA TODAY did was important to focus on these issues and it helped put pressure on HUD,” said Sarah Bolling Mancini of the National Consumer Law Center. “For many people, this will absolutely change their lives — allowing them to stay in their longtime home, rather than being foreclosed or evicted.” Meaghan McDermott, a reporter at the Rochester (N.Y.) Democrat and Chronicle, reported on the tragic drowning death of a 3-year-old boy in a restaurant’s grease trap. A $44 device would have prevented it. Within two days of publication, a state lawmaker said she would amend her proposed law to require the devices. I interviewed McDermott back in 2018 after she investigated the death of another 3-year-old. That investigation was a catalyst for reform of the county’s Child Protective Services department. It’s nice, and life-affirming, when politicians cite our work in calling for change. The Courier-Journal published an analysis comparing Kentucky’s $24 million settlement with OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma to Oklahoma’s $270 million settlement. “Why did Kentucky settle a case for 10% of the amount Oklahoma settled?” Kentucky’s Senate president asked while holding the newspaper. “Why did we have to wait for The Courier Journal to ask a question that we should be asking?” another state legislator said. Here’s the story. Here’s one for the cyber sleuths: A few hours after popular.info alerted Facebook to a “Police Lives Matter” Facebook page and others run by a Kosovo-based network, Facebook took down every page Popular Information flagged. (h/t First Draft News) If you have an impact story to share, email [email protected]. Anjanette Delgado is the senior news director for digital at the Detroit Free Press and freep.com, part of the USA Today Network, and the former digital director at lohud.com. Twitter: @anjdelgado. The Democrat and Chronicle and Courier-Journal are part of the Network. Gabriel Rom is a freelance journalist based in New York City. He can be reached at [email protected], www.gabrielrom.com or on Twitter at @GabrielRom1. ### By Anjanette Delgado The first question I ask when talking about impact journalism is who holds the power. Who has the power in the story? Who can make change? And who’s most affected by that? Questioning those in power is a no-brainer in investigative reporting — just as strategizing how to reach them should be when designing a story or project for impact. Cole Goins and Kayla Christopherson think about power, too, but they take a step back and look at the entire system. How are everyone and everything connected? Who holds the power in the system? And what role does journalism play in that? You might recognize some of this language: System. Role. Connection. Goins and Christopherson’s work — at the New School’s Journalism + Design hub in Manhattan, in newsrooms and at conferences — centers on systems thinking. Support comes from the Knight Foundation and the Democracy Fund. “We came to this sort of organically,” Christopherson said when we talked this fall. “My background is not in journalism but in systems thinking — systems thinking to understand complex processes.” Distributing the power

Systems thinking is a way of analyzing problems and structures by looking at how its interconnected parts relate. For example, your organs work together to digest food. I live in Detroit, where people worked together on the first assembly line to build cars. One of the most celebrated books on the matter is “Thinking in Systems” by Donella Meadows. (If you’d like to dig deeper, I suggest reading it or checking out these additional resources.) Meadows outlines 9 leverage points in a system — 9 places you can intervene — and ranks them from least to most effective. Fifth on her list is information flows — how information moves and who has access. That’s where journalism fits in. “The role of journalism is to provide communities with information,” Christopherson said. “By taking a systems approach to information, you are providing your communities with the most strategic information.” People can decide what to do with that information, said Goins, who cites the author David Peter Stroh as an inspiration here. “We’re just convening the conversation.” By focusing on that role, journalists begin to see the power they have in a system, in their communities, and how they can distribute the power by sharing information, by equipping people to make decisions instead of just engaging them. Christopherson said she’s starting to think, too, of what people do with the information as the end product rather than the journalism itself. That, she said, was a light-bulb moment. “When this happens you can be more transparent about what your goals are … and where people see value in your output,” Goins said. Goins is a journalist who once worked at the Center for Investigative Reporting, a newsroom often cited for its trailblazing work in impact tracking. He thinks of this work as “being more deliberate and active” about our roles as journalists. With systems thinking, he said, impact is not a single change but whether or how the larger system itself is affected. Equity and inclusion. Root causes. For example, after our corruption investigation the mayor resigned but has our work really helped to change the system to keep this from happening again? Remember that classic scene in the movie “Spotlight” where Liev Schreiber/Marty Baron tells the reporters to go after the institution, not the individuals? “Practice and policy,” he says. “Show me the church manipulated the system so that these guys wouldn’t have to face charges. … Show me that this was systemic, that it came from the top down.” We’re they’re headed Christopherson and Goins first spoke about systems thinking and journalism last summer at SRCCON in Minneapolis. They spoke again this fall, first at a Table Stakes convening in New Orleans in September and then at the People Powered Publishers Conference in Chicago in November. [1] [MORE: Designing for impact at SRCCON.] “I’m energized by depth of conversation and questions people are asking,” Christopherson said. “Clearly there’s a space for this kind of work in journalism. [SRCCON] gave us the green light to say let’s go deeper, make this more public.” Journalism + Design, led by founding director Heather Chaplin, introduces some of these ideas in its classes and for educators, too. A few directions they’re heading in: ● Rethinking the role journalists have and how they can use that power. ● Rethinking the structure within newsrooms so that decisions are more democratic than hierarchical, giving everyone some power and agency.[2] ● Bringing in community members to share the power.[3] “A different kind of information flow is just bringing people together who are in the same system but don’t normally talk to each other,” Goins said. ● Mapping the “wicked problems” in journalism and how they’re interconnected. “This is very much experimental,” Christopherson said. “Systems thinking is proven in other fields, but the idea of bringing journalism into that is very new.” “Everyone in the system has agency,” Goins said. “Part of this is discovery of what power I have to make change.” Clarification here: SRCCON wasn't our first session on systems + journalism. We began hosting workshops on systems thinking and journalism in mid-2018, and have so far held about two dozen workshops with journalists and newsrooms across the country. SRCCON was one of our first times focusing specifically on journalism and systems change, which is a direction we're trying to head more. Here are the notes from that session: https://etherpad.opennews.org/p/SRCCON2019-catalysts-for-change This is true, though at a higher-level, we're focusing on using systems thinking as a way to spark structural change internally. You could rephrase to something like: Giving journalists tools to think of their own newsrooms as complex systems and identify opportunities for structural change. I'd suggest rephrasing this to be more about how we're helping newsrooms use systems and stakeholder mapping as a strategy for taking a more active role in facilitating impact, something like: Supporting opportunities for journalists to convene and engage stakeholders across a particular system in surfacing and evaluating opportunities for structural change. Anjanette Delgado is the senior news director for digital at the Detroit Free Press and freep.com, part of the USA Today Network. Twitter: @anjdelgado. You can reach Cole Goins and Kayla Christopherson on Twitter at @colegoins and @kaylachristoph. ### By Erica Rosenthal

Charitable giving and philanthropy are as important today as ever. In the midst of the pandemic and national reckoning with racial injustice, Americans from all backgrounds are giving in different and important ways. Understanding these trends, how they are shifting and how media can and does influence the discourse is the subject of this Urban Institute podcast, featuring our Director of Research, Erica Rosenthal. She also gives a sneak preview into our soon-to-be-released research funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation on philanthropy and charitable giving in the media. PODCAST: Why Charitable Giving and Philanthropy Matter Today Erica Rosenthal is the Research Director for the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center Media Impact Project. ### |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed